Discourse” is nothing but all “written and verbal communication”. In line of Gramsci and later Foucault we have to understand “discourse” as “institutionalized” way of thinking, or in words of Judith Butler “limits of acceptable” speech. Its these limits which subverted in order to reach a true libertarian discourse. The discourse is controlled by means of “exclusion”, no other opinion simply exists. Foucault writes:

“Of the three great systems of exclusion governing discourse — prohibited words, the division of madness and the will to truth ———”

“——One can straight away distinguish some of the methodological demands they imply. A principle of reversal, first of all…. Next, then, the principle of discontinuity ….”

I am planning to do all this , i am trying to bring forward the “prohibited voices”, those which have been totally eclipsed in the society by the dominant discourse. This is not “endorsing” one and rejecting “others”, rather, its simply a act of breathing , an act of subversion ,of saying what is not pleasant to hear, Its simply an act of living in the rotten stagnant conformity.

One of the great “prohibiter” is “Islam” and “Honour of Prophet”, this brilliant article by Aatish Taseer tends to highlight the aspects of these two ideas which usually remain suppressed . A frank simple report but the one which shakes a lot of certainties. It was published in “Prospects”. The prose is enchanting, Taseer has a innocent frankness which simply is enlightening

“The Fastest Growing Religion of the World”

“Our soul, our blood, kind and gentle is our Prophet.”

A Damascene Conversion

Aatish Taseer

The last time I saw Isak Nilsen, we were eating okra and mutton in my flat near the diplomatic quarter of Damascus. The 22-year old Norwegian, who had been in Syria for four and a half months, seemed impatient to go before a sheikh and make the simple testimony—“There is no God but God and Muhammad is his Prophet”—that would introduce him to the society of the believers. Three days later he was on a plane back to Oslo, evacuated from a country where the faith put him at risk.

Isak’s Christianity was different from most of my European contemporaries. He was a theology student on his way to a career in the Norwegian church. He really believed that Christ had died on the cross for our sins and was the son of God. Yet now Isak was on the verge of converting to Islam, with its “clarity,” its “completeness” and its willingness to enter spheres of public life from which his church had long since retreated. Two days after our lunch the faith he was about to embrace did enter public life, but it was an entry far more violent than he would have liked. The same words that were to have been his conversion testimony had become the slogans of an angry mob attacking his embassy, burning his flag and threatening his friends.

For the past six weeks I had been in Damascus talking to young people about the place of religion in their lives. The Syrian capital is, to those interested in understanding Islam and Arabic, the key—what Boston is to liberal secular types. Abu Nour University, which reached its zenith under the late grand mufti of Syria, Sheikh Ahmad Kuftaro, is a favoured destination for students from non-Arab Muslim backgrounds hoping to gain or regain knowledge of the religion. On an average day Chechens, Indonesians, Pakistanis and British and American Muslims crowd the university’s corridors on their way to Koran and Arabic classes. The approach to Abu Nour is through a famous Damascus souk dotted with 13th and 14th-century minarets. Nearing the giant, still-new marble edifice, one begins to see bearded, robed and veiled figures from across the globe, standing out among the Syrians no less than Ella, my tall, blonde girlfriend.

The more secular Damascus University also attracts many foreigners for whom Islam holds a strong appeal, and it was among these students that I first experienced the city. I arrived in Damascus on a rainy Christmas eve after a gruelling bus journey from Aleppo, in northern Syria. I went to a flat in the embassy district that my friend Chad shared with Isak, the Norwegian student. Over the coming six weeks, Isak and I came to know each other reasonably well. That night he and a Norwegian friend of his were tucking into salmon and a bowl of gløgg, a Scandinavian winter drink. The three others in the room were my friend Chad—in Damascus to improve his Arabic—and two South Africans of south Asian extraction, brother and sister. The sister, Semeya, wore a headscarf and was bewitchingly pretty.

The more secular Damascus University also attracts many foreigners for whom Islam holds a strong appeal, and it was among these students that I first experienced the city. I arrived in Damascus on a rainy Christmas eve after a gruelling bus journey from Aleppo, in northern Syria. I went to a flat in the embassy district that my friend Chad shared with Isak, the Norwegian student. Over the coming six weeks, Isak and I came to know each other reasonably well. That night he and a Norwegian friend of his were tucking into salmon and a bowl of gløgg, a Scandinavian winter drink. The three others in the room were my friend Chad—in Damascus to improve his Arabic—and two South Africans of south Asian extraction, brother and sister. The sister, Semeya, wore a headscarf and was bewitchingly pretty.

Over the gløgg, Isak mentioned his plans for a career in the church. Inspired by his vocation and by being in the city where Paul had converted to Christianity, I suggested that we go out, despite the bad weather, to find a midnight mass. The two Norwegians were fired by the idea and we set out in the direction of the old city, passing Straight Street, the street with a kink described in Acts as “a street called Straight,” a remark which Mark Twain cites as the only bit of facetiousness in the Bible. Such is the religious diversity of Damascus that we confused Catholic churches with Orthodox ones, Greek ones with Armenian ones, and wound up, well past midnight, cold, wet and unblessed.

Over the next few days I spent a lot of time in this curious milieu with Chad and his circle, discovering the hamams and souks of the city that I was to live in for the next two months. It took me a few days to realise that there was an Islamic current running through many in the group. It was hippy Islam, if such a thing is possible. The gatherings of Chad and his friends were inter-religious, multi-ethnic and tediously respectful, but Islam was always present. It was in the sparseness of people’s flats, the fondness for facial hair in the boys, the studied, serene voices and the abundance of fruit juice. I quickly grew tired of it, and after a dry Christmas dinner I befriended Even Nord, Isak’s friend, a Norwegian with a glint in his eye and knowledge of the Journalists’ Club, a place where we could get a drink.

Like schoolchildren, Even and I had given the others the slip and were heading off for a beer when Semeya, the South African beauty, found us and pulled Even aside, appearing to scold him in low tones. She knew where we were going and felt “uncomfortable” about its environment. It was fascinating to watch her, almost self-consciously demure under her headscarf and long eyelashes; I wondered what emotional blackmail she was employing and to what spiritual end. At last, after withholding his purpose and describing the place as a cafeteria, Even managed to extricate himself.

But the Journalists’ Club is not a cafeteria. It is a large gloomy room with hideous blue and gold interiors that derives such popularity it has from being the sole drinking establishment in that part of town. Even and I settled down under the fluorescent glare and had just ordered a beer and a glass of wine when Semeya appeared again, looking like a terrified, hunted creature. She quickly came over to our table, fussing to Even about how uncomfortable she was. “I just don’t feel right,” she whispered. She addressed hardly a word to me and spoke to Even in Arabic, which I don’t understand. Then she produced a sheet of Arabic verbs and studied them silently for a while; and then as quickly as she had come she was gone.

It was over a drink with Even that I became aware of the strange appeal of both Islam and Semeya in his life. “In the west, we are all about rights,” he said, “but we have forgotten about limits.” He said he and Isak had both been impressed by Semeya’s spiritual quest. “She’s here only to develop her relationship with God,” he said, admiringly. It sounded like she had seduced them both with her piety.

What had seemed to me a fine example of female guile was to Even evidence of how Islam curbed the excesses of modern western life. “The only immorality in the west these days,” he said, “is to speak of morality. I am so tired of this hedonistic lifestyle, I want something simple.” He was blond, athletic and handsome, and knew a fair amount about Norwegian death metal music; I expect he also knew something about the western excesses of which he spoke. But I didn’t share his pessimism, and after a drink or two we parted ways. It was my first taste of this kind of talk. I had no idea how much more was coming my way.

The next day I left town and went travelling for two weeks with Ella. When I returned, I ran into Chad and Isak at an estate agent, where I was looking for a flat. Isak had his parents with him. The Eid holiday was beginning and they were about to set off around Syria. I learned from Chad that Isak, before the arrival of his parents, had been travelling with Semeya.

Once I had settled into an old 1920s flat, not far from the French embassy, I asked Even to take me to Abu Nour, the university where international Islam broods high up the hill overlooking Syria’s capital. I thought Even would be the perfect guide to this mysterious, slightly intimidating quarter. He spoke good Arabic; was, like Isak, his friend and apparent rival for Semeya’s affections, increasingly Muslim; and with a peculiar charisma moved through the dustier parts of the city like a favourite blond son. After lunch one day, he and I set out through the Souk Jouma. As we made our way past stalls full of dates, olives, meat and blood oranges, past electrical repair shops, camel butchers and a man drying trotters with a blowtorch, I caught my first glimpse of Abu Nour students. There were small Indonesians with conical hats and wispy beards, vast African women in coloured veils and pale Europeans with red facial hair. The scene culminated in a small square from where Abu Nour’s white minarets were clearly visible. The square was packed with internet cafés, Islamic literature and a store called Shukr specialising in stylish Islamic clothes for western markets.

We were looking for Tariq, a fix-it man known to all the new arrivals. We found him on one corner of the square, a big, meaty figure with a friendly manner. “Where are you from, brother?” he asked. “I welcome people from every country because everyone was very nice to me when I was in Europe. I can help you, brother, and unlike a lot of guides, I don’t ask for your money. What do you want? Arabic? Koran? A lot of people come here from all over the world—Africa, England, Pakistan—to learn about Islam.” Unlike a lot of guides who say they don’t want money, Tariq truly didn’t, which made me even more nervous. In a country where it is rumoured that 10 per cent of the population are informers for the mukhabarat, I was concerned that Tariq was making his money elsewhere. It was Thursday and we agreed to meet the next day before Friday prayers.

On the way back, Even suddenly grabbed my arm and we slipped into a side street off the main souk. Even knocked on a black metal door and after a short wait, a small Asian man in grey Arab robes opened the door. He hugged and kissed Even profusely. He welcomed us into a sitting room and then into a further room, which looked like a tiny presidential office. Above a big desk and chair there hung, on one side, the Syrian flag with a picture of the president, and on the other a flag I didn’t recognise: red stripes and yellow stars and moons on a black background. We were in the headquarters of the Pattani United Liberation Organisation, of which I had never heard, and the little man was its president in Syria. Cakes and soft drinks arrived and the man unburdened all the details of the plight of his people in southern Thailand. He produced his wife and a little baby a few minutes later. Then he insisted we watch a film about a massacre in Pattani, in which a soft-spoken American narrator told of the horrors of Thaksin Shinawatra’s regime in Thailand. When it was over, the little man said, “Pattani want peace, but Shinawatra want to make war.” At this he laughed maniacally and pointed to the wallpaper on his computer. “It say, ‘Thailand will be destroyed and Pattani will rise.’” Again he laughed his hellish laugh and we took our leave, Abu Nour and its environs now seeming to me like some rabbit warren of extras from a jihad film.

The next morning Tariq took me to the translation room of the mosque at Abu Nour, where you can listen to the sermons and prayers in a number of languages. On the way I confessed to him that I didn’t know how to pray. “No problem brother, we will teach you,” he said. We entered the great building with hundreds of other people. Tariq led me up a few flights of stairs on to a balcony, from where I could see hundreds of white caps below. I followed Tariq into an annexe where a handful of students were watching a sermon on television. Tariq sat me down next to a short, south Asian brother dressed in white. “Please brother, teach him to pray,” said Tariq, and with that he left. I greeted Mohammad, who turned out to be from Australia, and thanked him for his help as he passed me some headphones. When the sermon had finished, he suggested that we do our ablutions.

I followed Mohammad into the washing area. He taught me how to wash Islamically: my hands up to my elbows, my face, a portion of my hair and my feet up to my ankles. He seemed to notice that I was less diligent than he was, and he said, quietly: “The Prophet used to do it three times.” When we returned to the translation room, a few robed, bearded figures had come on to the stage. Mohammad whispered to me that Abu Nour often had guest speakers, and that today they had the grand muftis of Syria and Bosnia, as well as the Syrian minister of culture.

I put on my headphones and started to listen to an English translation of the words of Salah Kuftaro, director of the university and son of the former grand mufti. His speech, like those that followed—except for the grand mufti of Bosnia, who preached the need for understanding—was all incendiary politics. Each time the formula was the same: Islam is a religion of peace, tolerance and moderation, they would say (as if answering a counter-claim); a reference to the glory of the Islamic past and the need to guard against the enemies of Islam; then a congratulation to the present regime for doing so. Kuftaro finished by saying: “It is easy to get depressed in these times, to see the forces against Islam. The Islamic world is fragmented and divided. It is so because of the west and the influence of its ideas. First they rob us economically, then they rob our land, and once they have done that, they rob us culturally.”

After he had finished, we prayed. I had a rough idea of what to do and managed to get by without drawing too much attention to myself. When it was over, I was introduced to some of the brothers from Britain and America. Mohammad suggested I join them at the Kentucky Fried Chicken that evening, but I declined. As I walked back through the souk, I felt drained. The speeches had been so full of grievance, so closed to the idea of real reconciliation. I knew that in a country where the discussion of politics is forbidden, the mosques were the only outlet for these issues, but I still wondered why the preachers were so reliant on confrontation to get the message across.

I spent several days meeting privately with some of the people I had met at the mosque, trying to understand what had made them give up their lives in the west and turn to Islam. Simplicity, clearing away the clutter of modern life, was a big theme. Completeness was another: a single divine philosophy managing every aspect of life and conduct. Routine was another still: praying and fasting ordered the mayhem. And identity: feeling part of a universal brotherhood where other identities had failed. There were brothers like Fuad, a British Asian from Doncaster who had escaped his corporate job in Bristol to come to Abu Nour. “It was so grey,” he said. “The drive to work every morning, operating on mechanised time, arriving to find you have 200 emails. I realised that to succeed in that world, in the corporation, you had to serve the corporation. And for what? For money? Instead I chose to submit to something true, something with meaning.” There were many like Fuad.

Since arriving in Istanbul three months earlier, beginning a journey through the Dar al-Islam—land of the believers—that would also take me back to my own long-obscured Islamic roots in Pakistan, I had seen how Islamic “completeness” informed ideas of language, science and history. Khaldun, my Arabic teacher in Damascus, who was desperate to move to America or Britain to convey the word of Muhammad, showed me how Islam lived even in the pages of his English-language textbook. He pointed to a small multiple-choice exercise in which the author had suggested that in order not to be rude, it was better to say someone was not handsome rather than that he was ugly, or to say that someone was not interesting rather than that he was boring. “See,” he shouted, “this is like Islam! English is a moral language.” Zahir, the translator of the Friday sermon at Abu Nour, had shown me how science came from the Koran. Nadir, my guide and translator, showed me that history itself came from Islam. In a frustrated moment, he said: “We used to have a great history. Not before Islam of course, but since.” By “we” he meant Syrians, who a mile away had founded the Christian church, and who, a millennium before that, had invented the alphabet.

“This land has had a great history for thousands of years that pre-dates Islam,” I said.

“Yes,” Nadir answered, “an immoral history.”

I had never heard of such a thing, but Nadir’s idea, like Khaldun’s, was part of Islam’s all-encompassing nature. If you had it, you needed nothing else. “If I find one thing,” Nadir said, “one thing that the Koran doesn’t cover, I will renounce the faith.” But Nadir could never find that one thing because Islam served as the source of everything. Unlike Even, I was beginning to feel that this, not the hedonism of the west, was the real problem of limits.

It was during these disheartening discussions with Syrians and visitors alike that I saw Isak again. We arranged to have lunch in the old city, in a restaurant that had once been a stable. I brought Ella, and Isak was with Chad. I hadn’t seen Isak since that time outside the real estate office. His friendly face, supported by a physical and emotional solidity, made him the sort of person people like to trust. Seeing Isak, I had a thought I’d had before: he would make such a good priest.

“Does studying theology usually lead to a career in the Norwegian church?” I asked him.

“Yes, after the MA, which includes a year of training, you become eligible to join the church,” he said.

“Is that a route you plan to take?” Ella asked.

“Yes, well, actually…” he said, and then turned to Chad with a coy smile, as if about to make a confession of love for his friend, asking, “I can tell them, right?”

Chad shrugged his shoulders. “It’s up to you…”

“Actually,” Isak said, turning to Ella and me, “I’ve become more interested in Islam.”

“What has interested you?” I said.

“The fact that it handles politics more openly,” he answered. This aspect of Islam was precisely what was putting me off, but Isak felt that in the over-secularised environment of Europe, the church had lost its role as a forum on political issues. “Islam,” he continued, “discusses politics more honestly.” He also emphasised that he liked the prayers five times a day, that the faith had a tangible quality and ruled over all aspects of its adherents’ lives. I had heard this a million times before, but never from a potential priest and someone used to the vast freedoms of Scandinavia.

So great was Isak’s passion about Islam that Ella finally asked: “Would you think of converting?”

“I am actually in the process now,” came the reply.

I was sure the seductions of Semeya had played some part in this, although Chad assured me later that this was not the case. As I spoke more to Isak, he mentioned travelling to Palestine years ago on an inter-faith trip with Muslims and being struck by the passion of their belief. It was exactly this aspect that worried me about Isak’s conversion. I felt that it was Norway rather than the Abu Nour side of Syria that had found the proper role in life for faith. While the passion and fervour of deep faith attracted Isak, it unnerved me.

I asked what his parents thought about his conversion and he said they didn’t know yet. But his mother had returned to Norway from Syria with “sparkles” in her eyes. “It’s not like the politicians and press want us to believe,” she had told people back home.

“What isn’t? Syria or Islam?” I asked.

“Both,” Isak replied.

There was something touching about the openness of his thinking, his willingness to take on belief. More than he knew, the open society he had lived in had shaped his thinking and made the conversion possible. Yet had it been too open? Too diffident? So much so that he now wanted to embrace its opposite?

I asked him if he was worried that his faith would diminish once he was out of an Islamic environment. It was hard to imagine the ritual ablutions among the pubs and wooden Lutheran churches of Fredvang, his fishing village in Norway. “Well, I’ll pray five times a day,” he answered. “And I’ll have the Koran.”

I knew he meant it, yet I felt that Islam was so public a religion, so exacting in its control of the physical details of everyday life, that in distant, cold Norway, with no sound of the muezzin for miles, it would be harder to find the direction to Mecca. I saw Isak as a friend by now, and feared it would all lead to an ugly outcome: hysteria, breakdown, a loss of faith.

The next (and last) time I saw Isak, it was for lunch at my flat. The cartoon furore was brewing up and a Norwegian paper had just printed the images. Isak was critical of the paper’s decision. He said the publication was a small religious rag with a tiny circulation, one they scoffed at in Norway, and that its decision had less to do with free speech than with circulation.

Isak stayed with me most of the afternoon and we spoke again about his conversion. He said the most significant obstacle was a question on the nature of Christ. The Muslims treat him as a great prophet, and give him the title of Ruhollah, or spirit of God, but do not accept that he was the son of God and died for our sins. I said that purely for aesthetic reasons it would be sad to lose that story. Isak replied, “No Muslim could accept that Christ was the son of God because to them God is a flawless entity. He doesn’t come upon the earth and experience, hunger, poverty and death.” It was a conversation for which I had little training. My concern was that the faith—not the precepts but the feeling of faith, and its limitless quality in Islamic society—was overrunning Isak’s careful theological training. He admitted, “Lately, from friends and people I’ve been talking to, I’ve had more influence from the Islamic side. I feel like a split personality.”

The next day, the cartoons were the subject of the Friday sermon from the pulpit of almost every mosque in Syria. Even and I returned to the translation room at Abu Nour. From below, Kuftaro was speaking: “The Europeans are using all their power to destroy our faith. It is our Islamic duty to boycott all goods from these countries.” He compared Islam’s situation today to its situation in 7th-century Arabia, where it was also beset and surrounded by enemies. Not once did Kuftaro make any distinction between the papers that had published the cartoons and the countries themselves. “When our sanctity is oppressed,” Kuftaro continued, “we will sacrifice our souls, spirits and bodies for you, O Prophet.”

Even and I looked nervously at each other. It was chilling to think of identical sermons taking place throughout the country, attended by so many people. Demonstrations were now taking place every day outside various European embassies in Damascus.

After the sermon, brother Rafik, an African-American from Florida who had once told me to listen to the ringing in my heart that is Islam, defended the sermon. “Well they got their response, didn’t they?” he said. “If it’s response they wanted, they have it. There are men sitting on their embassies with AK-47s.” I questioned weakly whether threats and violence were a fitting response to what was indeed a provocation, but one within parameters western liberals considered legitimate.

“Yes, but who gave you that right, if not God himself?” brother Rafik replied. It was hopeless; he had yielded entirely to scripture.

Even and I went back to his house and he prepared lunch for a few friends. We had barely finished eating when we heard the next stage of “the response.”

“There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his Prophet,” rang out from the pavement below. We opened the window and saw that a small but fierce crowd of about 100 people, consisting of women in headscarves, children, old and middle-aged men and youths, was marching under the green banner of Islam in the direction of the French embassy. Some women from the crowd who caught sight of us on the balcony gestured to the girls to cover their heads. Even and I raced downstairs to see the demonstration.

If we hadn’t known what the context was, it would have been hard to make out the cause of the demonstrators. Their chanting, though strong and angry, was simple and repetitive: “Muhammad is the Prophet of God” again and again. The women who chanted had tears running down their cheeks and the message was so simple that a small child on someone’s shoulders led them in their divine slogans. His shrill voice raised their temperature and some at the front of the crowd began to scuffle with the police standing in front of the embassy. They pushed harder against the line of police, but they didn’t have enough momentum or mass to break it. One demonstrator threw some garbage at its steep concrete walls.

It was pathetic to see this crowd with its one slogan yelling angrily at an edifice that did not answer back. It was all they had understood of the situation, all they had been told: the enemies of Islam had directed an offence against them and it was their Islamic duty to respond. They knew nothing of the modern systems from which the provocation had emerged nor how to distinguish between the institutions that were accountable and those that were not.

Suddenly a Syrian friend of Even’s appeared from the crowd. The man had been part of the demonstration, which had gone from the Danish embassy to the French. He was in a state of exhilaration, laughing and joking at Even being a Norwegian. We followed him deeper into the crowd, but they were pushing against the police line again and I stopped. Even and his friend went closer to the front.

Suddenly a Syrian friend of Even’s appeared from the crowd. The man had been part of the demonstration, which had gone from the Danish embassy to the French. He was in a state of exhilaration, laughing and joking at Even being a Norwegian. We followed him deeper into the crowd, but they were pushing against the police line again and I stopped. Even and his friend went closer to the front.

Then with no warning, the friend turned around and addressed the crowd. “This is my friend. He is a Norwegian and a good man.” A menacing silence came over the crowd. I feared for Even’s safety. The friend picked Even up on his shoulders and said: “Speak for your country.” Even, if he was scared, showed no sign of it. He took in the crowd for an instant and then addressed them in Arabic. “This is just an embassy,” he said, in a loud clear voice. “It is not actually the country. This incident is the result of lack of understanding. We need to understand each other better. Then we will have the chance to live in togetherness and we can show proper respect to you. Inshallah, Inshallah, Inshallah.” The crowd roared in approval and someone shouted, “He accepts Islam.”

Addressing an angry crowd in a language that was not his own was an achievement for Even in itself, but the message that had come so simply to him was far

Addressing an angry crowd in a language that was not his own was an achievement for Even in itself, but the message that had come so simply to him was far

beyond anything the crowd had come up with. His message was full of diffidence and sympathy, keen not to blame but to comprehend. In the west such words would be clichéd; in the Arab world Even’s statement resounded with freshness.

We went back to Even’s house afterwards with his Syrian friend. “I wish I could have said more,” said Even, the adrenaline still strong in his voice. “I didn’t have the words. What I really wanted to say was, ‘We know you’re angry, but we still don’t know why.’”

We knew still less the next day, because the feeling of faith had broken its banks and submerged its own precepts. Even walked with the crowd that set fire to his own embassy. Pretending to be a Swede, manhandled and accused, at one stage he feared the crowd would turn on him. Teargassed by the police, he sought refuge with the wounded in a mosque. But when he returned to my flat, the detail that had impressed itself on him was that the crowd had prayed in the street before attacking the embassy, crying, “Our soul, our blood, kind and gentle is our Prophet.”

Some of the Norwegians of Damascus were to have a dinner that night, but it was cancelled as the rioting continued into the evening. As the news made its way across the world, Norway announced it was evacuating its citizens. By 4am, the first planes had started to leave. It was sad. I knew many of them. They were the best of the international lot: the majority had come with an idea of public service and they were the most keen to be part of Syrian life. Even decided to stay. He felt he had many Syrian friends who would protect him should things get ugly. Isak also wanted to stay, but his parents disagreed. The next morning he called me to say that he was leaving within the hour because of fears for his security. “I’m sure things will be fine in Damascus,” he said apologetically, “but now there’s this small, 1 per cent doubt in my mind

A study of discourse emerging from ruling elite of Pakistan, the PML and colonial administration which they inherited from Colonial administration suggest an obsession with monism themes as opposed to pluralism. Jinnah’s slogan of “Unity, Faith and Discipline” itself speaks of need to “unify and control”. The slogan relates more to ideologies of totalitarian regimes of Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany than to the Liberal tradition of Western Europe to which Jinnah is said to be trained in. Ethnic identities became the “others” of Muslim identity and as a result an existential threat the new state. The question of national rights was diverted by Jinnah’s stern warning against the “evil of provincialism”, the need to construct a “unified culture” so strong that a man as modern as Jinnah who took up the case of muslim socio-cultural rights in India, stood in Dacca and thundered “Urdu Urdu and only Urdu!” a language which was not the language of even 0.2% of Pakistanis at the time Those who demanded an equal status of Bengali along side Urdu were to called traitors and communists. After Jinnah’s death things became worse and PML which lacked any popular base in East and West Pakistan joined hands with Clerics and Islamic Fundamentalists whom Jinnah thoroughly despised. Jinnah’s handpicked Prime Minister Nawabzada Khan Liaqat Ali Khan, a member of feudal aristocracy passed the Objectives Resolution and state acquired an ideological character.

A study of discourse emerging from ruling elite of Pakistan, the PML and colonial administration which they inherited from Colonial administration suggest an obsession with monism themes as opposed to pluralism. Jinnah’s slogan of “Unity, Faith and Discipline” itself speaks of need to “unify and control”. The slogan relates more to ideologies of totalitarian regimes of Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany than to the Liberal tradition of Western Europe to which Jinnah is said to be trained in. Ethnic identities became the “others” of Muslim identity and as a result an existential threat the new state. The question of national rights was diverted by Jinnah’s stern warning against the “evil of provincialism”, the need to construct a “unified culture” so strong that a man as modern as Jinnah who took up the case of muslim socio-cultural rights in India, stood in Dacca and thundered “Urdu Urdu and only Urdu!” a language which was not the language of even 0.2% of Pakistanis at the time Those who demanded an equal status of Bengali along side Urdu were to called traitors and communists. After Jinnah’s death things became worse and PML which lacked any popular base in East and West Pakistan joined hands with Clerics and Islamic Fundamentalists whom Jinnah thoroughly despised. Jinnah’s handpicked Prime Minister Nawabzada Khan Liaqat Ali Khan, a member of feudal aristocracy passed the Objectives Resolution and state acquired an ideological character.

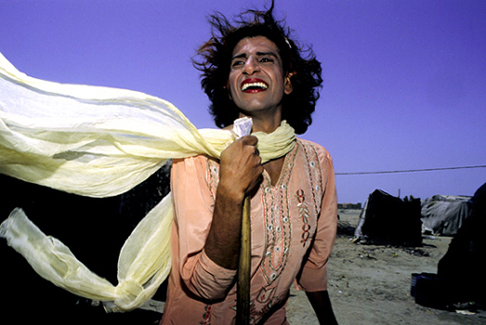

There has been little serious discussion of this SC ruling online or in the print media: no speculation whatsoever over the meaning of gender in Pakistan, or whether this ruling is right in creating a hijra subject for the purposes of bureaucracy. What is going to constitute ‘the Third sex’? And what happens to those who do not qualify for this category? What about those ‘gender-confused’ people who do not want to be identified as ‘Third sex’, preferring instead to be identified as ‘male’ or ‘female’?. According to the article quoted above, the hijra are ‘left by the society to live by begging, dancing and prostitution’, to be exploited by the ‘self-styled guru’ – does it mean that after this ‘social uplift’ program, they will be made to give up their lifetyle? What if they can’t? Does discrimination go away after formal barriers to progress have been removed, or does it merely become invisible and more difficult to fight? With the avenus of empowerment formally open to them, wouldn’t the society find it easier to blame them if their ‘begging and dancing and prostitution’ continues? Will they be persecuted or will we realize that a ‘respectable’ life is just not possible for the hijra without a radical change in the society, its institutions and maybe our ideas of ‘respectable’?

There has been little serious discussion of this SC ruling online or in the print media: no speculation whatsoever over the meaning of gender in Pakistan, or whether this ruling is right in creating a hijra subject for the purposes of bureaucracy. What is going to constitute ‘the Third sex’? And what happens to those who do not qualify for this category? What about those ‘gender-confused’ people who do not want to be identified as ‘Third sex’, preferring instead to be identified as ‘male’ or ‘female’?. According to the article quoted above, the hijra are ‘left by the society to live by begging, dancing and prostitution’, to be exploited by the ‘self-styled guru’ – does it mean that after this ‘social uplift’ program, they will be made to give up their lifetyle? What if they can’t? Does discrimination go away after formal barriers to progress have been removed, or does it merely become invisible and more difficult to fight? With the avenus of empowerment formally open to them, wouldn’t the society find it easier to blame them if their ‘begging and dancing and prostitution’ continues? Will they be persecuted or will we realize that a ‘respectable’ life is just not possible for the hijra without a radical change in the society, its institutions and maybe our ideas of ‘respectable’?

The Progressive left led a heroic struggle against the Neo Fascist Zia ul Haq, resulting in one of the most brutal crackdown against them, hangings, torture,murders,exiles, lashes—. Fahmida Riaz , Kishwar Naheed stood up against this tyranny , the result was the emergence of a radical feminist discourse that was modernist and progressive and which challenged the Islamist discourse on woman.

The Progressive left led a heroic struggle against the Neo Fascist Zia ul Haq, resulting in one of the most brutal crackdown against them, hangings, torture,murders,exiles, lashes—. Fahmida Riaz , Kishwar Naheed stood up against this tyranny , the result was the emergence of a radical feminist discourse that was modernist and progressive and which challenged the Islamist discourse on woman.

Heroine of the “new Right”, its fashionable these days to slander and dismiss Ali in almost all progressive circles of Europe. The problem unfortunately will not disappear by this continuous “Tabbara” on her. The lacuna within the progressive left ,which has sealed its lips in name of “anti imperialism” on fundamentalism, freedom of expression, and Islamic roots of violence and subjugation of women, has to be filled. The alliances from Lebanon to Islamabad with Islamic fundamentalism have to be broken and progressive position be taken on feminism and other “transitory demands”.

Heroine of the “new Right”, its fashionable these days to slander and dismiss Ali in almost all progressive circles of Europe. The problem unfortunately will not disappear by this continuous “Tabbara” on her. The lacuna within the progressive left ,which has sealed its lips in name of “anti imperialism” on fundamentalism, freedom of expression, and Islamic roots of violence and subjugation of women, has to be filled. The alliances from Lebanon to Islamabad with Islamic fundamentalism have to be broken and progressive position be taken on feminism and other “transitory demands”. This article by Ziauddin Sardar tend to expose the contradictions in the Islamist discourse, the assumptions about Islam which have been taught as “laws”. “The demolition of Babri Mosque” in India and alleged grand conspiracy to demolish “Dome of Rock” in Jerusalem have been used as “validaters” in Islamic discourse to prove “unity of whole world” against Islam. To destroy Islamic Identity , culture and existence. In the racist Islamist zeal no one mentions the demolition of Muhammed’s history from Saudi Arabia. Romila Thapar once commented that religion extremism is always “ahistorc” and it later becomes “Anti historic”. Sardar touches on the issue to “destroying history” by Islamists. On the whole this article too subverts and challange the dominant discourse on Islam and Islam’s political identity in Modern times. History is so much dreaded by Islamists because a simple historical analysis will show that theological roots of Islamism are not in Islam but in the Kharjites heresy and European Fascism.

This article by Ziauddin Sardar tend to expose the contradictions in the Islamist discourse, the assumptions about Islam which have been taught as “laws”. “The demolition of Babri Mosque” in India and alleged grand conspiracy to demolish “Dome of Rock” in Jerusalem have been used as “validaters” in Islamic discourse to prove “unity of whole world” against Islam. To destroy Islamic Identity , culture and existence. In the racist Islamist zeal no one mentions the demolition of Muhammed’s history from Saudi Arabia. Romila Thapar once commented that religion extremism is always “ahistorc” and it later becomes “Anti historic”. Sardar touches on the issue to “destroying history” by Islamists. On the whole this article too subverts and challange the dominant discourse on Islam and Islam’s political identity in Modern times. History is so much dreaded by Islamists because a simple historical analysis will show that theological roots of Islamism are not in Islam but in the Kharjites heresy and European Fascism. The more secular Damascus University also attracts many foreigners for whom Islam holds a strong appeal, and it was among these students that I first experienced the city. I arrived in Damascus on a rainy Christmas eve after a gruelling bus journey from Aleppo, in northern Syria. I went to a flat in the embassy district that my friend Chad shared with Isak, the Norwegian student. Over the coming six weeks, Isak and I came to know each other reasonably well. That night he and a Norwegian friend of his were tucking into salmon and a bowl of gløgg, a Scandinavian winter drink. The three others in the room were my friend Chad—in Damascus to improve his Arabic—and two South Africans of south Asian extraction, brother and sister. The sister, Semeya, wore a headscarf and was bewitchingly pretty.

The more secular Damascus University also attracts many foreigners for whom Islam holds a strong appeal, and it was among these students that I first experienced the city. I arrived in Damascus on a rainy Christmas eve after a gruelling bus journey from Aleppo, in northern Syria. I went to a flat in the embassy district that my friend Chad shared with Isak, the Norwegian student. Over the coming six weeks, Isak and I came to know each other reasonably well. That night he and a Norwegian friend of his were tucking into salmon and a bowl of gløgg, a Scandinavian winter drink. The three others in the room were my friend Chad—in Damascus to improve his Arabic—and two South Africans of south Asian extraction, brother and sister. The sister, Semeya, wore a headscarf and was bewitchingly pretty. Suddenly a Syrian friend of Even’s appeared from the crowd. The man had been part of the demonstration, which had gone from the Danish embassy to the French. He was in a state of exhilaration, laughing and joking at Even being a Norwegian. We followed him deeper into the crowd, but they were pushing against the police line again and I stopped. Even and his friend went closer to the front.

Suddenly a Syrian friend of Even’s appeared from the crowd. The man had been part of the demonstration, which had gone from the Danish embassy to the French. He was in a state of exhilaration, laughing and joking at Even being a Norwegian. We followed him deeper into the crowd, but they were pushing against the police line again and I stopped. Even and his friend went closer to the front. Addressing an angry crowd in a language that was not his own was an achievement for Even in itself, but the message that had come so simply to him was far

Addressing an angry crowd in a language that was not his own was an achievement for Even in itself, but the message that had come so simply to him was far